What is Product-Based Planning?

Product-Based Planning is a longtime hallmark of PRINCE2. It consists of four steps:

- Write a Project Product Description, which is a high-level description of customer expectations.

- Write a Product Breakdown Structure (PBS), which is a logical hierarchy of the project’s deliverables.

- Write a Product Description (PD), which is a concise but complete verbal definition of what has to be delivered by the project.

- Create a Product Flow Diagram (PFD), which identifies the order of precedence of products and their components or constituents.

BTW, the PMI PMBoK knows something called a “Work Breakdown Structure” which comes quite close to the PBS idea, in fact, there should be a 1:1 relation between the details, i.e., for every item in the PBS there should be (at least) one task to deliver it.

How do I implement Product-Based Planning?

I implement PBP by implementing the four steps from above, where step 1 and step 3 effectively are boiling down to writing a word document. I know you can do it!

How to write a Project Product Description?

Well, write a word document. Some templates can be found on the web.

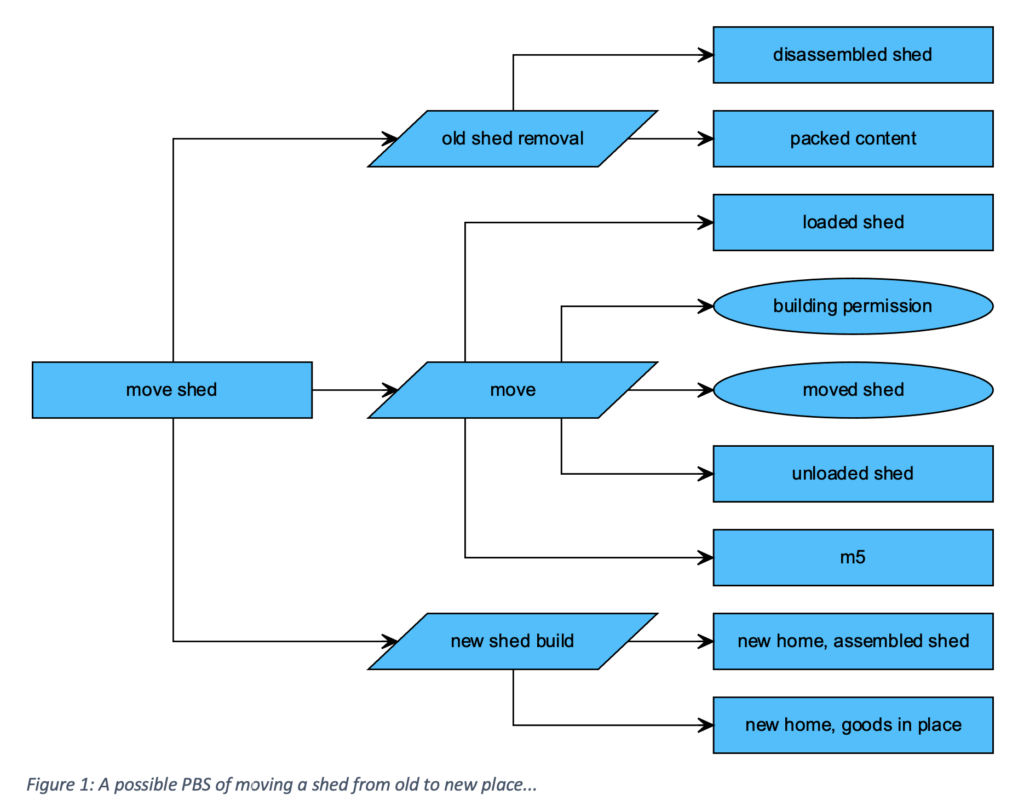

How do I do a Product Breakdown Structure?

By learning from examples. Well, here comes the example: We want to move a shed from place A to place B. What would be a good PBS?

Before we start we should define different node shapes for different classes of products (or deliverables):

- Logical groups are shown as parallelograms.

- External products (delivered not by the project but consumed by it) are shown as ellipsoids.

- Management products are not filled, all other products are filled (with non-white).

We see that our total outcome consists of three logical products groups (the parallelograms). For the sake of simplicity, we divide the complete hut into just two entities: the shed shell and its content. And we omit the management products (plans, reports, documentation, etc.)

Moving the shed is a bit more complex, since we foresee the need of a permission to build the hut at the new location, and we do not have a truck, thus an external mover will be involved. These are thus marked with an ellipse.

How on earth how did I create it? Well, I started my favorite text editor (sublime) and entered this:

digraph pbs {

splines=ortho

rankdir="LR"

node [margin=0.1 fontcolor=black fontsize=12

shape=rect style=filled

arrowhead="vee" fontname="Arial" fixedsize=true

width=2.5 shape="rect"

fillcolor=deepskyblue1 ]

edge[arrowhead="vee"]

p [label="move shed"]

o [label="old shed removal" shape="parallelogram"]

o1 [label="disassembled shed"]

o2 [label="packed content"]

m [label="move" shape="parallelogram"]

m1 [label="loaded shed"]

m2 [label="building permission" shape="ellipse"]

m3 [label="moved shed" shape="ellipse"]

m4 [label="unloaded shed"]

n [label="new shed build" shape="parallelogram"]

n1 [label="new home, assembled shed"]

n2 [label="new home, goods in place"]

p -> {o m n}

o -> {o1 o2}

n -> {n1 n2}

m -> {m1 m2 m3 m4}

}

…and pasted this into this: https://dreampuf.github.io/GraphvizOnline/ (or http://magjac.com/graphviz-visual-editor/)

In fact, the data seen above is written in a graph language called DOT (https://graphviz.org) and with this or a command line tool you can generate wonderful scalable vector graphics (SVGs), which can be viewed in any modern browser or may be imported into word.

How to write a Product Description?

Well, write a word document with a table with two columns: “product name” and “product description”, and you should be fine.

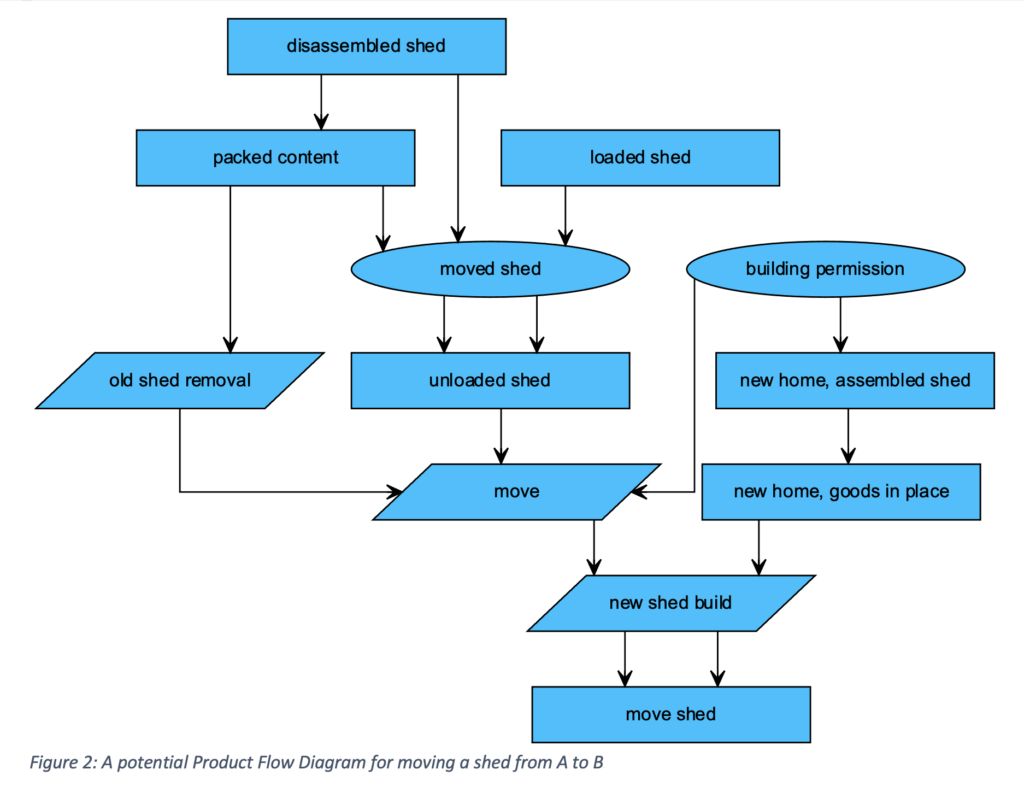

How could I write a Product Flow Diagram?

Easy:

digraph pfd {

splines=ortho

rankdir="TD"

node [margin=0.1 fontcolor=black fontsize=12

shape=rect style=filled

arrowhead="vee" fontname="Arial" fixedsize=true

width=2.5 shape="rect"

fillcolor=deepskyblue1]

edge[arrowhead="vee"]

p [label="move shed"]

o [label="old shed removal" shape="parallelogram"]

o1 [label="disassembled shed"]

o2 [label="packed content"]

m [label="move" shape="parallelogram"]

m1 [label="loaded shed"]

m2 [label="building permission" shape="ellipse"]

m3 [label="moved shed" shape="ellipse"]

m4 [label="unloaded shed"]

n [label="new shed build" shape="parallelogram"]

n1 [label="new home, assembled shed"]

n2 [label="new home, goods in place"]

o -> m -> n -> p

o1 -> m3 -> m4

o2 -> m3

o1 -> o2 -> o

m1 -> m3 -> m4 -> m

m2 -> m

m2 -> n1 -> n2 -> n -> p

}

What should you learn to understand the DOT language? Here is my concise list:

- Start with PBS digraph <NAME> {}. This will generate an empty directed graph.

- Insert your products into the braces, one per line. The format is

<PRODUCT NAME> [label = “<TEXT”]. In graph theory these products are called nodes. - Insert tree relationships, e. g., product-> component 1, one per line. In graph theory these relationships are called edges. Since we have a directed graph, these edges have start and an end, marked by an arrow or the like.

- If you like to manipulate certain attributes, you either change them in the nodes, or you insert a node item to change the default behavior of all nodes. The same holds true for edges.

- RTFM.